When I first read the synopsis for Tinā, my first thought that this was yet another heartwarming tale about a teacher who inspires their students.

While this is true of Tinā, unlike other films in the genre, the protagonist, Mareta Percival, is not gungho about transforming her students’ lives. Instead, audiences receive a film where the teacher does not suffer a saviour complex but authentically champions for the right to preserve one’s identity.

When we are first introduced to Mareta, we see her in the midst of the typical after-school routine in a local school. It is 2011, and just moments later, Mareta’s world crumbles around her as Christchurch experiences one of its worst earthquakes. While Mareta escapes unscathed, her daughter is killed. This kickstarts an all-consuming grief that sees Mareta withdraw from life.

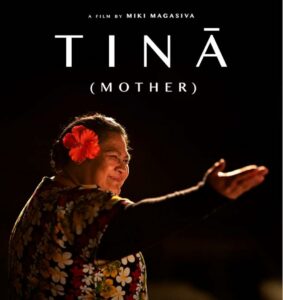

Fast forward to three years later and Mareta finds herself in a job she wasn’t intending on getting – a substitute teacher role in a private school. In the rigid, monotone world of elite education, Tinā is a burst of colour both literally and figuratively. Her refusal to bend to the school’s rules eventually finds her starting a choral group which focuses on Samoan music.

To be clear, Mareta is not teaching Samoan music to be anti-establishment. She’s teaching it because that’s what she knows and loves. However, Mareta’s unconventionality soon raises the ire of the stiff upper lips of the school.

And this is a constant fixture of the movie. Despite what’s happening around her and to her, Mareta is steadfast in maintaining her identity – a proud Samoan mother who feels a deep love for her heritage.

Tinā means mother in Samoan. True to her moniker, Mareta is motherly, gradually extending her aiga (family network) to include her poor little rich kids. She nurtures without coddling, balancing kind warmth with firm reprimands.

It would be easy to paint Mareta as a generously loving soul. After all, that’s what normally sells an “inspiring teacher” movie doesn’t it?

Mareta’s understandable post-trauma reticence brings depth to her character. I understood Mareta’s motivation for wanting to push the talented Sophie (Antonia Robinson) to greatness. She is seeking redemption on behalf of her deceased daughter. As a mother, I could feel her pain.

Anapela Polataivao played Mareta beautifully, breaking our hearts in moments of Mareta’s despair and bringing us tears with her unfiltered comebacks. Seeing her deadpan delivery of comebacks soothed me – Mareta’s going to be okay.

I’d call Tinā a roller coaster ride but that would imply a jerky, fast paced tale. Instead, Tinā is quietly fluid, taking your heart through ebbs and flows. The movie doesn’t swing from one extreme to another. Instead we get shades of different emotions in one scene, such as comic relief from the witty quips in serious moments.

In particular, I have to commend director Miki Magasiva’s deft handiwork, extrapolating intense emotional scenes from mundane experiences. It is the personification of the grief process, where one small thing can trigger an episode of heartache.

We often talk about how representation matters on the screen. Tinā delivers that on all fronts – she is a Samoan, a mother, a teacher, a survivor all in one. She makes no apologies for who she is and reminds us that we shouldn’t either.

Tinā is now showing at Luna Palace Cinemas.